For the first time in seventy years, the world will witness the crowning of a British monarch. Coming from a land without kings and queens, I’ve seen how chaotic a transference of power can be. For the sake of a weary world, I hope this transition goes well.

The coronation of King Charles III will begin with a golden carriage and solemn procession. After the preliminaries of hymns, prayers, the people’s acceptance, and his oaths, the archbishop will anoint him. Afterward, he will receive the regalia associated with his secular role. This ritual is called the investiture, and the Church will give Charles the ring, sword, crown, scepter, and rod. Each item has symbolic significance related to governance in faith, to protect, and with glory, justice, and virtue.

Medieval English Coronations

Current media about the 2023 coronation touts the tradition going back nearly 1000 years ago to Edward the Confessor. Yes, but…

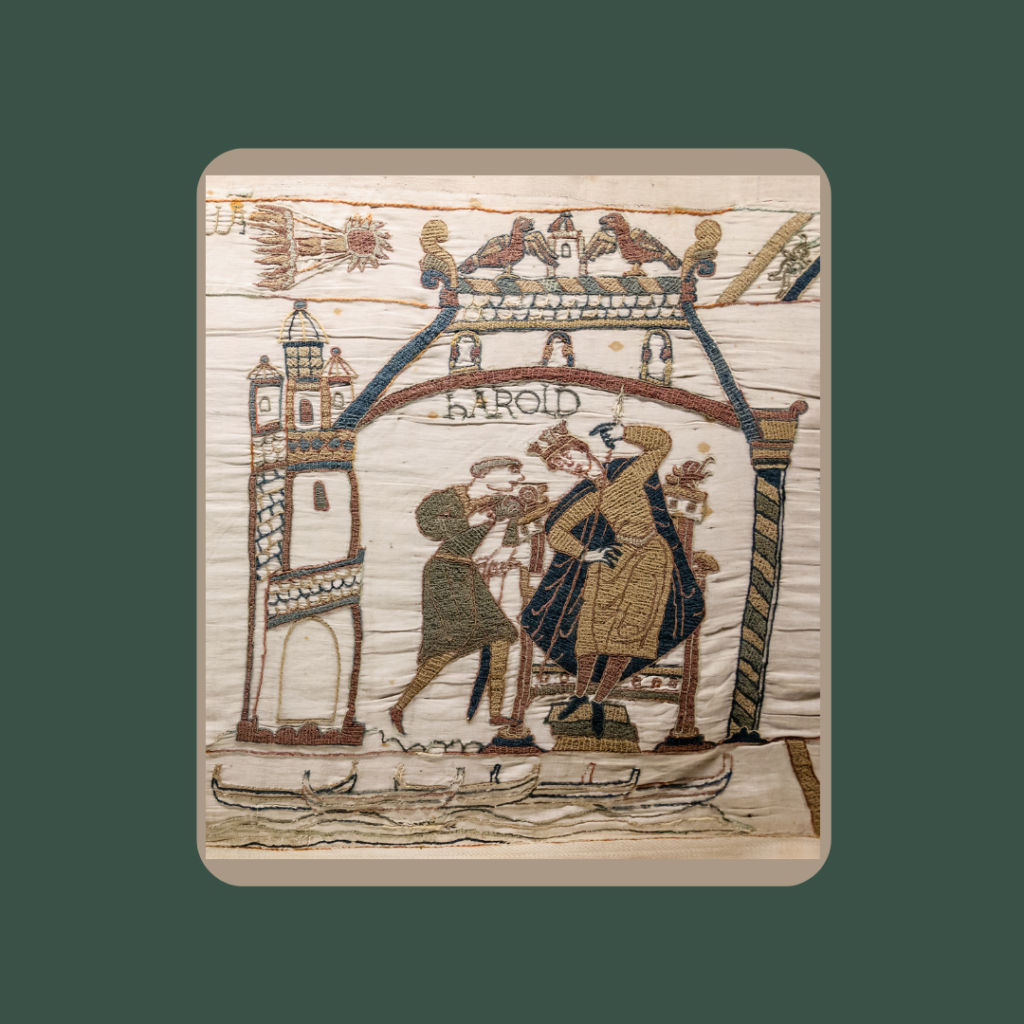

In medieval England, the coronation, a religious ritual, usually occurred during High Holy days, Christmas, Epiphany, or Easter. Nearly ten months after being proclaimed king, Edward the Confessor was crowned on Easter, the holiest of holy days. His successor, Harold Godwinson, received his crown on Epiphany, 1066, the same day he buried Edward. While some claim it was a blatant power grab, Harold’s coronation may have followed an ancient practice. Importantly, it gave Harold an opportunity to establish his reign and policies with England’s earls and thegns drawn together for Edward’s funeral.

King Edward died without leaving an heir, launching a scramble for the crown that left a deep scar on the land and the hearts of all involved. The French-speaking Normans invaded, Harold died, and William of Normandy became England’s king. Today, people still debate the impact of the Normans on the English. Anglo-Saxon pride is alive and well. Norman arrogance is, too. The battle continues. Laws, village practices, and local events are still measured in subtle degrees by those battle lines, despite the inclusion of diverse populations.

Most people are irked by invasion forces, whether the invaders are Persians bludgeoning Greece, Europeans decimating indigenous peoples in the Americas, or Russians stomping into Ukraine. So it takes more than a photo opportunity of the “victor” stroking an adorable puppy to calm a torn and troubled land. It takes years, perhaps centuries. But sometimes, ritual, pomp, and ceremony can bring about a temporary cease-fire, a breathing moment, and a vision of a united land. William clearly knew the significance of his coronation and set about to blend English and Norman traditions.

William’s Coronation

William’s coronation on Christmas Day, 1066, came at a notable time. Normans had established markets from Sicily to Constantinople. The Western Church had begun restructuring, and new political and theological ideas emerged.

That year, a spectacular set of circumstances coalesced. Halley’s Comet provided a celestial warning of Harold’s doom, the Pope gave William his papal ring and banner. Invaders attacked England in the North, drawing Harold away from the southern coast a few weeks before William’s fleet landed.

Despite Harold’s dramatic victory near York, a remarkable march, and a defense that nearly broke William’s soldiers, Harold fell at Hastings, and William the Conqueror arose victorious.

From the start, William invited English and Normans to plan the coronation. The English might have hoped William would go away. William’s followers may have urged him to ignore the details, boasting the throne was a right of superior might. It is likely that William saw the coronation as a means to unify a kingdom from disparate pieces and make it his own.

What William Changed

William incorporated English rituals established as far back as Edgar [BCE 957], eight kings before Edward. These rituals demonstrated an unbroken, inherited succession and validated his claimed right to rule over the “Angles and the Saxons.”

His coronation began when the bishops led him into Westminster, replicating Edward the Confessor’s procession. Cleverly, William had his French-speaking and English-speaking bishops demand all present formally accept the new king. A public, vocalized affirmation came from the French practice and remains part of today’s ritual. Some historians believe that Edward’s coronation had a similar moment, but that component is implied, unlike William’s coronation, when the shouts raised well-documented alarms.

The established coronation prayer cited the new king’s father. Since William was the bastard of a Norman Duke, the paternal connection became a general reference to a hereditary right.

William also introduced the Laudes Regiae, which remains part of the ceremony to this day. The hymn carried forward from Charlemagne’s coronation and sung in Normandy on major feast days was altered by William. The Laudes erased any mention of the French king, Duke William’s overlord. Instead, it recognized William explicitly as king–an equal to all other secular rulers in Western Christendom.

The prayer also mentioned William’s queen. Although Matilda of Flanders did not receive her crown until May 1068, her coronation proclaimed that God had placed her over the people and that she shared in royal dominion. No queen had shared royal power before.

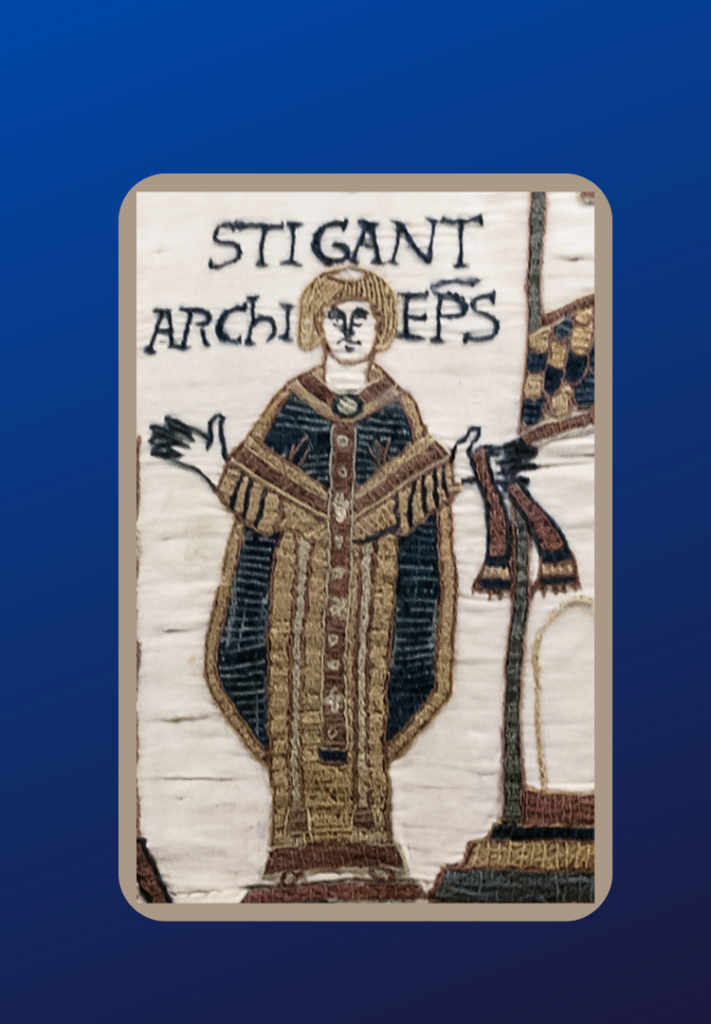

William broke precedent when he chose the Archbishop of York over the Archbishop of Canterbury to preside at the coronation. Five popes had excommunicated Archbishop Stigand of Canterbury. William did not want a questionable Archbishop to anoint him, which might lead some people to question his sovereignty.

The legacy

William’s changes to the coronation ceremony appear minor until one knows what came decades before and what came centuries afterward. William’s reign had lasting ramifications not merely for England, but throughout Western Christendom, in ways few people at that time could imagine.

Nearly a millennium later, kings are no longer absolute or semi-absolute rulers. Although coronations seem less important than in the past, the brilliant colors, pageantry, and solemnity bear the testament of a cohesive people. Via television, anyone can witness the passage of faith and duty to Charles III, who embodies the symbol of a people and the history that made Great Britain a force that influenced many lands. His coronation is a historical moment. We might never see another, given the potential for monarchies to vanish.

*Pun intended.

References:

Barlow, Frank, Edward the Confessor, (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1970)

Douglas, D. C., William the Conqueror, (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964)

Stenton, F. M., Anglo-Saxon England, (Oxford, 1971)

2 responses to “Kings, Queens, and Puppy Dog Tales*”

Thanks so much for this. I found it very informative and interesting.

Very interesting telling me things I did not know.