When I teach others to write, I tell them to put “the dead body” in the beginning. That is my metaphor for the central hook or dilemma that will spur people to read further. So, watching King & Conqueror, I laughed out loud at the opening battle scene strewn with corpses and again when the camera panned over bodies floating in a river. Sorry, I’ve got that kind of humor.

Episodic Drama

BBC/CBS produced this eight-part drama, staring James Norton and Nikolaj Coster-Waldau. It aired in the UK in August 2025 and became available in the US in November 2025.

The series is set in the 11th century, a period I write about. I ignored the gross historical inaccuracies by reminding myself that this is theater and not a documentary. I forgave the creators. After all, I am not a historian, I write historical fiction, too.

Like most fiction writers, I work in solitude, extrapolating from my own experiences to imagine what motivated historical events. My perceptions are always colored by my own time and mindset.

A television series is a collective effort requiring a team discussing every aspect of the production. In this case, the team included the director, creator, and writer, all praised for their dramas. I imagine a smoke-filled room, guys tossing ideas around, arguing, laughing, drawing, or jotting notes about the story.

21st Century Imprints

I wanted to see how the team’s version of events that occurred 1000 years ago would reflect the Zeitgeist, the thoughts, ideas, and beliefs of our historical period.

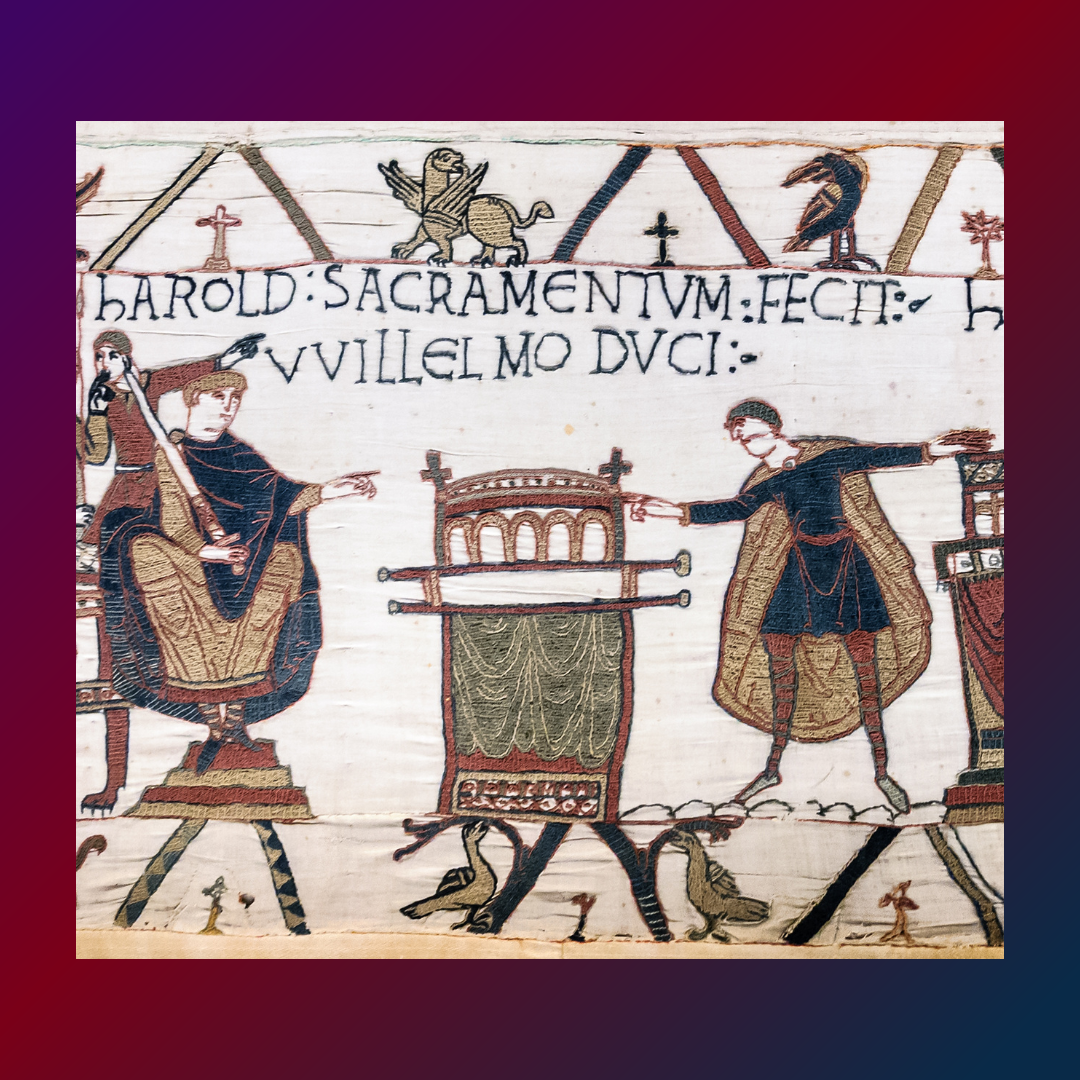

King & Conqueror culminates with the Battle of Hastings. In 1066, the actual King Harold Godwinson of Wessex, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, fought to defend his crown against William the Bastard, duke of Normandy, who claimed the throne was his.

The series is a guy flick. Two men who could have been friends and allies fight to the death for a prize. The creative team entwine the protagonists in parallel personal challenges, presumably to highlight their similarities. Harold and William send their reckless brothers away, both dodge assassins, love their wives, and care about their children. Both cry, lie, and kill to achieve their ends.

Striving for emotional depth, the team perverted historical fact. Judith dies in childbirth giving Tostig a reason for his betrayal. Harold tries to rescue his wife Edith, an attempt to provide a punch later when Harold marries Margaret of Mercia for an alliance. William’s desire to protect his son from future assassins provides the justification for killing the king of France. Harold is mired in guilt for killing his brothers. William feels the weight of sacrificing his loyal liegeman to kill the baron of Brittany.

It is a challenge to make the medieval world relevant to present-day people. I appreciate that the creators changed the names of historical personages so viewers would not be confused. The series included other modern conventions. Religion is absent except when used to make King Edward a delusional madman, as a tool for punishing recalcitrant siblings, to hand over a crown, and to spread myths about God’s will. Homosexuals are acknowledged. Everyone can read. Power alone is the prize.

I’m glad that the creators included talented actors of all sizes, shapes, and colors. Few viewers who decry the use of these actors criticize the women characters, who are feisty, strong, can fight, kill, and rule empires.

Story Choices

Some story choices irked me. Within the first five minutes, Harold’s brother Sweyn deflowers a bride. I gave the creative team credit for having the viewers learn about the rape that occurred off-screen, rather than giving us a graphic scene. Still, I wondered why they chose to repeat a mythic “Right of The First Night,” (droit du seigneur, or jus primae noctis) rather than present the actual salacious history. Did the creative team intend to “normalize” the notion that any rich or powerful man has a “right” to grab any woman by her genitals?

The team had Matilda, William’s wife, torture someone. It was a device to get a prisoner to reveal information that would spur the rest of the story. Another character could have achieved the same result. Having females torture others seems to be a popular trope among male writers these days.

And what’s with the matricide? Queen Emma is bludgeoned to death by her son, King Edward. He blames his mother for the deed, and, of course, his wife absolves him. Reinforcing typical mankeeping expectations, or a warning to remind strong women to shut up?

Outcome

According to broadcastnow.co.uk, a BBC period drama costs between £1 million and £2 million per hour. Very costly, especially when these episodes are filled with bad sets, wasted scenes, insipid dialogue, and characters as hollow as artificially “intelligent” robots trying to act human.

One-thousand years later, the actual history still resonates. Yet, the characters of Harold and William as depicted in King & Conqueror seem no different than the tech barons, the billionaires competing for dominance, those guys who sacrifice truth for profits, who think governance is software code to be rewritten.

Then again, perhaps BBC/CBS and the creators never gave their production a thought beyond ticking the boxes for minimal marketing appeal.